While the humans strain to find the best position from which to take their photographs, the mountain goats stand silent. One man decides to see how close he can get, camera in hand, prompting the goats to flee. Other visitors let out sounds of disappointment, condemning the man for his selfishness. Yet the goats do slowly return to where the visitors can view them, and their return prompts the same wonderment as before, the same magnetism that pulls the camera.

While the people are in awe of (or perhaps just entertained by) the goats, the goats do not appear to return the sentiment. Mountain goats have strangely expressionless faces for mammals, and their snow-white fur gives them an otherworldly quality, adding to the sense that they do not occupy the same plane of existence as the humans. Who knows how the goat sees the human? They are not even mountain goats unto themselves. How would the goat draw a line that distinguishes its world from that of the humans or even one that could distinguish itself from its environment?

There are other sights to be seen and more images to be taken on Mount Evans, though animal life undoubtedly provokes the most emotion. A marmot is also on the peak until two young visitors chase it away. A pot-bellied man attempts to sit on a ledge on which there is a sign describing facts about the peak in anticipation of visitors. The man fails to mount the ledge and stumbles. He is attempting to capture a photograph.

On top of Mount Evans, one will find the ruins of a modernist structure referred to as Crest House. These ruins represent the highest altitude at which a business structure had been built in the United States. Though it was little more than a gift store and restaurant, known for its coffee and doughnuts, Crest House’s stone ruins evoke an image similar to those of Caspar David Friedrich for visitors accustomed to Tyvek-laden contemporary structures. That Crest House lies in a state of ruins stimulates this feeling of deep time, of man’s transitory existence compared to the quiet relentlessness and integrity of nature. Yet it was not actually “nature” that destroyed the Crest House. The building was destroyed in the late 1970s, an accident in which an employee of the Evergreen propane company left a safety valve unsecured, resulting in a fire. The modernist ruin is the result of clumsy negligence rather than romantic nature.

Mount Evans is one of Colorado’s tallest peaks and its scenic byway is the highest paved road in North America. The road snakes through the landscape of the Arapahoe National Forest, past Echo Lake. On the day of my visit, it was hard to find good parking. There was an atmosphere of inconvenience, the result of having to continually circle the parking lot, competing for the next available spot. The access granted by technology is undermined only by the presence of those others who also are granted access by the same technology.

Perhaps it might seem that the solution to this problem of overcrowding would be the building of more parking lots, but this could only be achieved by paving over that which we all drove here to see. One would arrive at Mount Evans only to see the parking lot that it had become. America’s highest altitude parking. The presence of culture disrupts our expectations of nature. Silent thoughts pray for some intervention that would remove the others, no need to know the details. Democracy for me but not for thee.

Susan Sontag articulates the democratic nature of photography in her canonical On Photography. I consider her declaration that “to collect photographs is to collect the world,” when I see the cameras of Mount Evans, clearly outnumbering the goats. One can just barely take a picture on the peak unimpeded by the presence of others taking pictures. The nature of Mount Evans is seen through the temporary cracks between culture. The image of nature must be stitched together from all these chance views. Nature as collage. Photography becomes a means to write the difference between culture and nature.

Why should we not consider the presence of these human-car-camera hybrids as something natural? Romantic naturalism is tied to an outdated form of ethics that places too much emphasis on individual human agents. We are just as well off elaborating an ethics for the Pine Beetle. Across the Colorado Rockies, Pine Beetles are thriving in the prolonged heat caused by Global Warming, destroying forests. From the perspective of the Pine Beetle, all is well. These are ideal conditions. They are not equipped with the means of recognizing that their consumption outpaces the growth of the trees they consume. The forest exceeds their comprehension. If Pine Beetles are not moral agents, then why assign a morality to the visitors of Mount Evans? Like the Beetles, these agents simply express their agency within a given environment. When Margaret Thatcher tells them that there is no such thing as society, they respond accordingly, anticipating that they should be the only ones who have access to the peak.

But who is out there warning the visitors of Mount Evans that there is no nature?

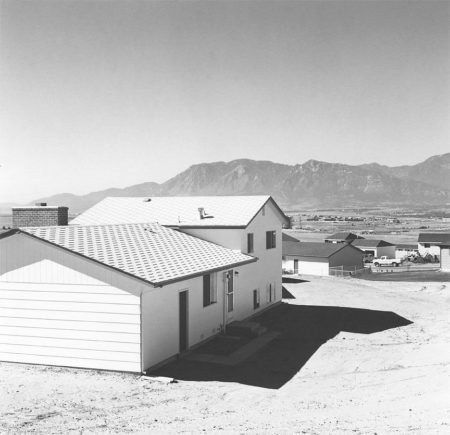

I always experienced nature as something in Colorado, though I wasn’t certain where it was located. I assumed it was located in the mountains. Nature was something advertised. Nature could be experienced in a specific section of Dick’s Sporting Goods. Nature was a product, not an environment. I grew up in the suburbs of Colorado Springs, with an ideal view of the Rockies always in sight but Constitution Ave. in my backyard. I saw more car accidents than goats. I never connected with nature photography until I saw the images of Robert Adams.

1968

Gelatin silver print,

11 × 14 inches

Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

© Robert Adams

Adams does not resist the presence of culture in his images of nature. Not that he is celebratory of this presence. In his book Why People Photograph, he expresses a bitterness at the developments occurring in Colorado in his time, the highways and corporate farms as well the plutonium contamination from the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant (140). He expresses the desire to be alone that characterizes the decedents of those who followed Horace Greeley’s command to “go West young man” as a means of escaping city life. He laments the changes in Rocky Mountain National Park, complaining, “there was more privacy in City Park in the middle of Denver than in walking the high peaks” (158). Adams reads like an old-school environmentalist you’d expect in a nature photographer from the 70s, a type of aging liberal who lives in Colorado and New Mexico, concocting a unique spiritualism founded on the Judeo-Christian tradition, with hints of Zen, a sincere caucasian’s interpretation of Indigenous American culture, and hearty doses of land-art.

So why did Adams seem to so frequently make culture’s intervention into nature a theme? Why the images of Colorado Spring’s suburbs? Adams briefly comments, “the condition of the western space now does raise questions, nonetheless, about our nature” (140). I think those questions are principally what Adam’s photographs try to answer. I can’t tell whether, in referring to “our” nature, he is writing about so-called human nature or the state of nature we collectively imagine to exist outside ourselves, particularly in places like Colorado, and I prefer this ambiguity. It was in Adam’s photography that I first saw a recognizable “nature”. These photographs just barely predate me. Adam’s pictures are about the loss of his world and the origin of mine. These were the first images I had seen that situated me in a place and a history.

Contrast the photographs of Adams with those of Jeff Mitchum. Mitchum is a contemporary nature photographer who, though he might never be seriously considered a figure of historical relevance, absolutely can be described as successful in economic terms. I only heard about him due to my working at a company that photoshop-enhances, prints, and frames Mitchum’s images. Hundreds of his prints passed through my hands, as if I were destined to pay attention whether I wanted or not.

I absolutely connect these images and those of photoshopped models. Mitchum’s is a nature compensating for lack. It’s as if his camera somehow reveals that the world isn’t as beautiful as it should be. Photoshop is Mitchum’s Viagra. His is a nature that does not exist except as an image. It’s a nature that is desirable because it cannot be had. Yet because it can be imagined in digitally-modified “photography”, it can be sought after, and when it isn’t found, its absence is blamed on the presence of humanity.

Who has been left unaware that the bodies in advertisement are often biological impossibilities? Yet just because it is an obvious and easy point of criticism doesn’t make it irrelevant. Our comfort with manipulated photographs seems akin to our acceptance that “politicians lie” as a mundane truism. Furthermore, increasing awareness of the proliferation of manipulated photographs does not result, necessarily, in making these images less attractive. One can now masturbate to CGI anime girls and deepfake celebrity porn. The limbic system doesn’t care about the difference between real and false. Rather than turning us off, photo-manipulation stimulates a lust for technologies that might exponentially construct ever more attractive images of nature. Nature photography in the style of Mitchum is just barely about nature. It’s rather a spectacle of technology, of HD digital cameras, RAW files, high chroma pigment prints, and of plexiglass finishes.

This nature cannot be seen from atop Mount Evans. The mundane thusness of the peak remains, attractive or unattractive as the case may be. The mountain goat might look you in the eye with barely a spark of acknowledgement. The ancient adaptations, the twisted shapes of 1,700-year-old Bristlecone pines, the patterns of climate all go on without attention paid to the iPhones and Hondas that set up temporary camp. The mountain goat does not appear offended. Instead of bitterness, I feel curiosity at the transformation brought on by the consumer camera, the democratic road, and the mass distribution of nature.

It seems a capitalism-democracy hybrid is implicitly secular. It grants access to the peak to all those who can can afford a car. It grants the means to “collect” the peak to those who can afford a camera. The idea that a pilgrimage might be demanded, that the peak might expect a cost is almost eliminated. If a pilgrimage does remain, it is that of overcoming an economic barrier, of affording access to technology, and in such cultural products as The Pursuit of Happiness this process appears sacred. Otherwise the peak has been brought low and domesticated. This democratization might be offensive to individual visitors who all believe themselves to be exceptional and thus worthy of the peak in ways that should be denied to others. But the full parking lot attests to the expectation that the mountain should be as accessible as the mall.

A visitor falls off a cliff, is struck by lightning, or is attacked by an animal on occasion. This is the sacrifice the mountain demands so that it might retain at least the potential of being enchanted. It’s the evidence that nature, in the Heart of Darkness sense, potentially is out there. The misfortune always happens to someone you don’t know, lending evidence to the sheer massiveness of humanity. Regardless, we enter the mountains knowing we could, though most likely will not, be its victim. That something terrifying could happen means that something beyond the image remains. The mountain retains a potential that exceeds human comprehension. Awareness is on the faces of those who die taking selfies next to steep edges.

Works Cited

Adams, Robert. Why People Photograph: Selected Essays and Reviews. New York, NY: Aperture, 1994.

Susan Sontag, “On Photography (Excerpt),” 2010, http://www.susansontag.com/SusanSontag/books/onPhotographyExerpt.shtml.

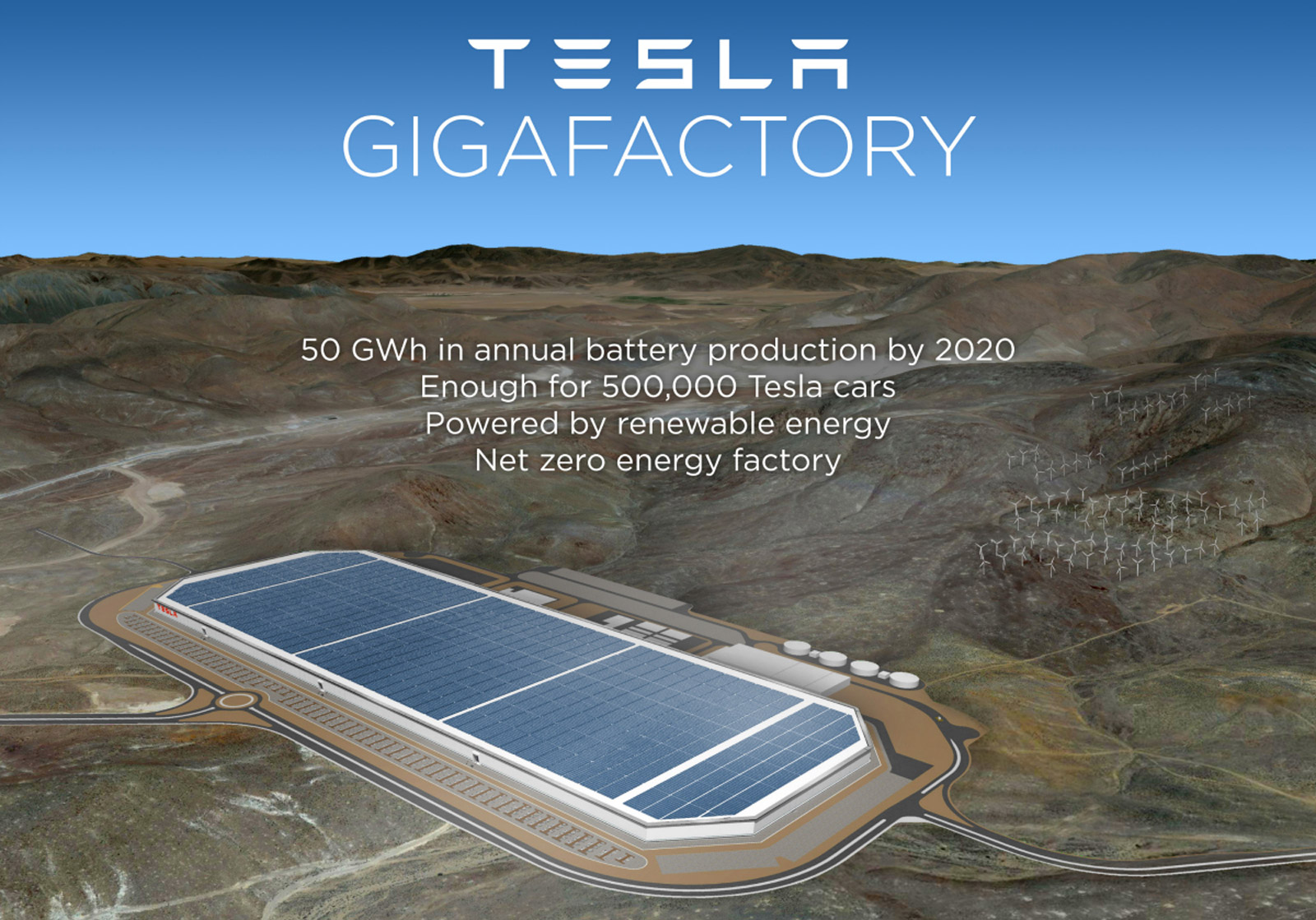

I propose Walmart-sublime in response to Rem Koolhaas’s observations on mega structures, such as server farms like the Tesla Gigafactory. He describes the development of these structures in the Nevada desert as a type of urbanization “almost without people”, robotic urbanization that does not need humans, though upon which humans have grown to depend. Koolhaas relates the vastness, an almost overwhelming sense of scale of these structures, something usually connected to the sublime, though the original sublime overwhelming emphasized nature. This is obviously not J.M.W. Turner’s sublime.

I propose Walmart-sublime in response to Rem Koolhaas’s observations on mega structures, such as server farms like the Tesla Gigafactory. He describes the development of these structures in the Nevada desert as a type of urbanization “almost without people”, robotic urbanization that does not need humans, though upon which humans have grown to depend. Koolhaas relates the vastness, an almost overwhelming sense of scale of these structures, something usually connected to the sublime, though the original sublime overwhelming emphasized nature. This is obviously not J.M.W. Turner’s sublime.

One thing concerns me about cities like Memphis and Louisville. Their reliance on one industry, in this case the shipping industry, seems no different than Detroit’s reliance on one industry: the car industry. Detroit is perhaps the most important American city to

One thing concerns me about cities like Memphis and Louisville. Their reliance on one industry, in this case the shipping industry, seems no different than Detroit’s reliance on one industry: the car industry. Detroit is perhaps the most important American city to