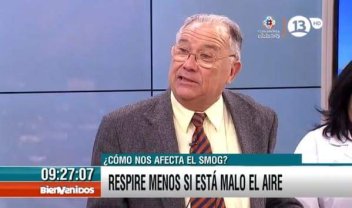

Chilean humor is very particular. What I’ve gathered is that Chileans find discrepancy funny: when words fail to honestly or accurately describe an image, or when words are used in an evasive way, the way politicians avoid saying truths that everyone knows. They also enjoy mocking ridiculous solutions to real problems. I recall one news clip in which the anchor spoke on pollution in Santiago and recommended it was healthier to breathe less. And it seems Chileans tend to laugh, when no too inappropriate, at those things that are supposed to be taken seriously, mostly because they are supposed to be taken seriously.

What’s greatest about Chilean sense of humor is that Chileans love laughing at themselves. Not in the cruel way Americans seem to laugh at themselves, which doesn’t feel like laughing at themselves at all but more like laughing at the half of America they don’t like. Chileans are more like someone laid back enough to acknowledge and genuinely find humor in his own mistakes.

Chilean sense of humor is also absurdist.

Of the most iconic products of Chilean comedy is 31 Minutos, produced by Aplaplac. 31 Minutos takes the form of a news broadcast, hosted by puppets. Presented as a children’s show, it first aired on Chile’s broadcast television station, TVN, in 2003. It became an instant classic after the first episode. How could it not? This first episode answered a question that we all have: where does all the shit go? In a segment entitled: La Ruta de la Caca (the trail of poop), reporter Juan Carlos Bodoque goes on a journey to show people where all their waste goes and how it gets there.

Bodoque is one of most appreciated characters. He is a dedicated, straight-talking reporter, the kind of journalist we deserve but rarely get. When at the end of his report, head anchor Tulio Triviño refers to human waste with the more gentle “caquita”. Bodoque corrects him, “caca, Tulio. Let’s call it what it is.”

There is an aspect of 31 Minutos I’ll never be able to appreciate like a Chilean. For example, many character are based on real figures in the news. The pretentious, inconsiderate, self-adoring head anchor Tulio Triviño is a parody of Bernardo de la Maza. Bodoque parodies Santiago Pavlović who seems so committed to the truth that it looks like he lost an eye for it. Policarpo Avendaño is Italo Passalacqua. La Ruta de la Caca was broadcast at the same time such stories as the trail of silk (exploring silk trade) were popular on Chilean television. These references are local, thus inaccessible for foreigners.

What is accessible is the general acknowledgement of the proliferation of bullshit, something that seems as ubiquitous as God and Google. It is important, however, to see 31 Minutos in context. 2003, when 31 Minutos was first broadcast, was just thirteen years after democratic vote put an end of Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship. The campaign to vote “no” on the continuing of the dictatorship is heavily indebted to the late 80’s early 90’s aesthetic. I half expect Micheal Jackson to pop up out of nowhere, drinking a Crystal Pepsi, in a commercial promising that happiness is coming. And the graphic with the word “no” underneath a rainbow is one of the most discrepant images I’ve ever seen. It’s the first time I saw the word “no” presented as a positive. Yet it was a positive in its context in a way we who have never lived under a dictatorship can never understand.

Many Chileans alive today can say they lived under a dictatorship, including the producers of 31 Minutos. A military dictatorship does not exactly produce most convenient atmosphere for subversive humor. I once heard comedian John Cleese describe, ironically, how one must crack down as all forms of humor for being subversive if one wishes to be dictatorial, “for humor will be the only form criticism will take, since if they express their criticism outright you will come down on them like a ton of bricks.” And like a ton of bricks the Pinochet government did come down on all critics, leaving a legacy of death and missing people. There are people alive today, not old, who still don’t know what happened to their mother or father.

This is not to praise the communist government that preceded Pinochet or the governments prior. I have no authority behind my opinion at all, nor do I have the right to speak on a struggle that never affected me. It is clear, however, that Chile has suffered its fair share of bullshit.

Bullshit is, basically, what 31 Minutos is about. Tangananica Tangananá is a song about meaningless obstinance, the insistence on defending positions that, to the outside world, are almost indistinguishable. Yo Opino is a homage to all those people who feel the need to express their opinion, even if not asked for. Sung by Joe Pino (a character I love enough that I have him on my key chain): “Yo opino que opinar es necesario porque tengo intelegencia y por eso siempre opino.” (My opinion is that to express your opinion is necessary because I am intelligent and because of this I always express my opinion.) He also states that his reading of the newspaper is what makes him so smart and he believe the government is right and wrong depending on which side you are on (this is his opinion, of course.)

Here you might wonder if this is really a kids show? The truth is: it is and isn’t. It’s basically Chile’s Pee Wee’s Playhouse: something adults will to get out of bed to watch with their kids (even if they didn’t have kids). Something about 31 Minutos evokes a sense of nostalgia that speaks to the adult’s sensibility as much as child’s. The puppets belong to the world we had back when we were kids and Sesame Street taught us our alphabets. And that they are Chilean, so specifically belonging to the local world of things accessible only to Chileans, is perhaps more enjoyable to Chilean adults who’ve had the time to self-reflect.

I see 31 Minutos as a tonic, doing something to address that “what now” period that follows the end of something dramatic. The “vote no” commercial promised happiness, a world with people dancing and smiling and hugging each other. Of course it is questionable if this world ever came or if it, too, was bullshit. Chileans still live under the same constitution drafted during the dictatorship. Something that has changed, however, is that Chileans’ years of pint-up anger and disappointment has found expression, and of course if found expression in humor. Humor is how we disarm. 31 Minutos especially serves the generation of those who were either unaware or were not born during the dictatorship. In making fun of all the bullshit and in building something out of the local means available, Aplaplac has contributed to building Chilean culture post-dictatorship.

I’ve heard it said that one can tell someone what has been through significant pain from one who hasn’t by a person’s attitude. If an individual wants to get over his or her pain, it’s because the pain is significant. The pain is a legitimate obstacle. It does not serve the individual in any way. If s/he wants to dwell, s/he is not truly in pain. S/he actually gets something out of the situation s/he is in, even if that something is not clear. I don’t assume this meaning was intentional, but there is a moment at the end of the 31 Minutos movie where Bodoque frees some other puppets. “We’re free!” they cheer. Then they stand there, in the open cage, staring blankly ahead. “Get out of the cage,” says Bodoque. “That’s what freedom means.”

one who hasn’t by a person’s attitude. If an individual wants to get over his or her pain, it’s because the pain is significant. The pain is a legitimate obstacle. It does not serve the individual in any way. If s/he wants to dwell, s/he is not truly in pain. S/he actually gets something out of the situation s/he is in, even if that something is not clear. I don’t assume this meaning was intentional, but there is a moment at the end of the 31 Minutos movie where Bodoque frees some other puppets. “We’re free!” they cheer. Then they stand there, in the open cage, staring blankly ahead. “Get out of the cage,” says Bodoque. “That’s what freedom means.”